Bogotá and Antioquia, Colombia’s biggest city and department, sent thousands of messages to the public to inform them that they were exposed to Covid-19. They did it using information that was not enough to make such a claim like that, obtained from millions of people who gave it up unwittingly.

Click here to view original post

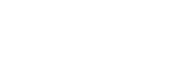

From early May, some citizens from Bogota, the capital and most populated city of Colombia, began to see advertisements on their Facebook and Instagram phone apps. It was an alarmist image, with the “alert” sign and the Mayor’s office logo: “It is very likely that you have been in contact with someone infected with COVID.”

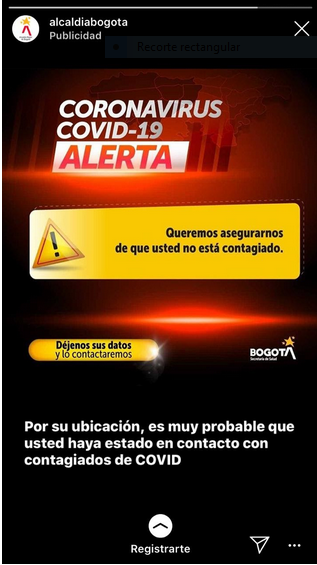

In Antioquia, Colombia’s biggest department (state), the alert comes on text message: “You may have coronavirus,” in capital letters. (Bogota is not a part of Antioquia).

A report published by the Karisma Foundation published on July 3 shows how several Colombian local authorities are using digital advertising geo-reference tools to display these warnings, get information on the virus’s progression, and identify the contacts of people infected with the virus.

This use of technology by authorities amid the pandemic had never been identified before. It is based on data that is often collected without users’ knowledge, through applications people use every day.

The ads simulate an “exposure notification”: a notice that the user was in contact with someone infected. They aim to make citizens contact the health authorities, either through a form or a phone number.

Both Antioquia and Bogotá use geo-referenced advertising to serve these ads but in different ways. As explained to Karisma by the Bogotá Health Secretariat, the notices are directed through geo-referencing to users in areas where there are “contagion spikes.”

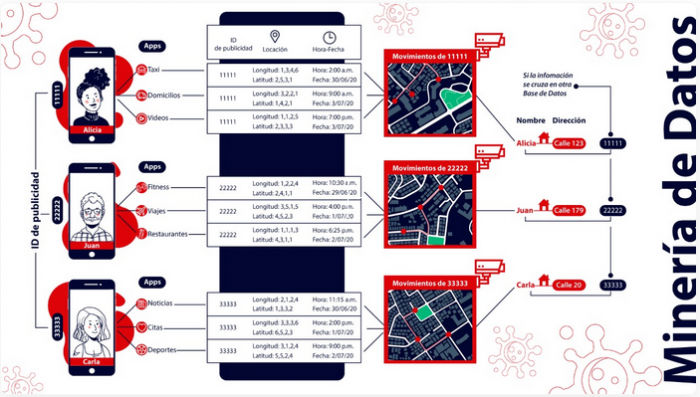

In Antioquia, the process is more thorough. Luis Gonzalo Morales, the former manager for coronavirus containment in the department, said at a press conference on May 19 that the department will use the devices’ unique advertising identifiers of people infected with the virus to track their contacts digitally.

As part of this process, the authorities obtain information from infected people’s cell phones. “Once we initially located positive cases, and got their phones’ IDs, we will ask the Google tool where those phones move, and which other devices were less than 10 meters away from them for more than 30 minutes,” he said.

In an official letter sent to the Karisma Foundation, he government did not clarify how it obtains IDs from infected people or how it gets access to the IDs from people near someone with the virus. However, they most likely get them through digital advertising companies, which usually use these data to sell targeted advertisements.

In fact, a company from Bogota named Servinformación collaborated with Antioquia in the development of the tool — its logo appeared at the press conference — and has helped the Bogotá Mayor’s Office to measure the extent to which citizens are complying with mandatory quarantine. That company sells geolocated data services to digital marketing companies.

A data scientist for this company, Emiliano Isaza, was a co-author of an academic paper detailing how advertising IDs could work as a ‘radar’ of the virus. These data would be useful to “detect social contexts associated with the transmission of the virus in near real-time and to answer questions retrospectively, to understand processes that facilitate or prevent the spread of the virus,” they claim.

Bogota stopped showing these notices after being contacted by the Karisma Foundation, but Antioquia continues to do so.

How does the ID work?

What Morales calls “the ID of the cell phones” is the advertising identifier. This code identifies devices for digital marketing operations but does not include information about their users’ identities.

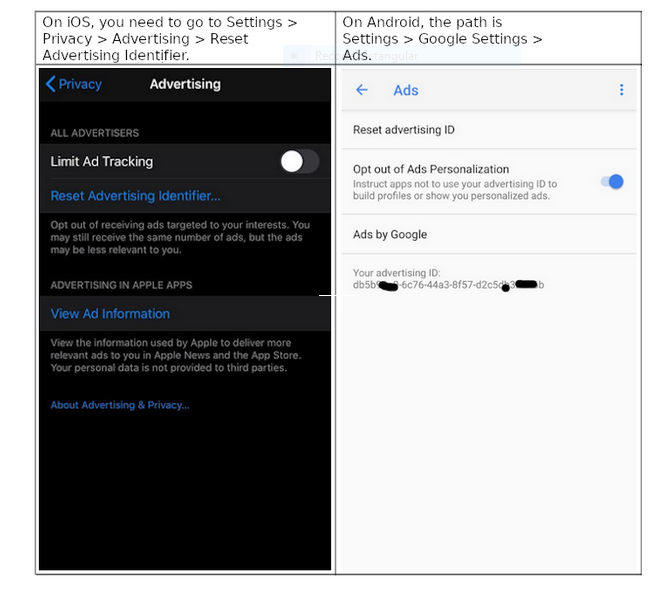

All smartphones have an advertising ID. It is called Android Advertising ID (AAID) on Google’s mobile operating system, and Identifier For Advertising (IDFA) on Apple’s iOS. Users cannot prevent these IDs from being used to obtain information about their phone use.

Google and Apple include these IDs in their operating systems because they are crucial to the economy around mobile applications and data-driven advertising. They allow developers to monetize their apps in exchange for data from users: what applications do they use, what websites they visit, what they buy, what their location is, and so on.

App developers then sell these data to data mining companies who process it and resell it to digital advertising companies, which in turn use it to offer ads targeted by variables like gender, age, or preferences. This industry is estimated to be worth US$ 80 billion a year.

The issues

Antioquia’s approach seems like an alternative to Bluetooth contact tracking, which, according to the National Institute of Health, Colombia currently does not do —even though the CoronApp Colombia application has tested at least two technologies for this purpose, and it is included in the terms and conditions of the Colombian national COVID app.

The thing is, these data are not precise enough to do that. Still, they could be useful to track a user’s daily routine and identify them relatively simply —even though the database is anonymous— since it includes the user’s location several times a day.

The cell phone detects the location with the same instruments and techniques it uses when the user calls a taxicab or asks directions on a map app. As most users surely have experienced, the accuracy is not the same every time, since it varies according to factors such as the density of wireless connections or the surrounding buildings.

Karisma argues that the severity and “alarmism” of the messages are not justified. “They are causing fear to people by showing them a misleading message when it is not true that they know what they say they know,” the report says.

Despite that, these identifiers could still be used to follow people. With a database similar to the one used by the administrations of Bogotá and Antioquia, The New York Times identified several users using the places where they spent several hours in the morning and night.

Singling a person out requires a piece of information that links their identity with their location, such as a company’s directory or a city’s yellow pages. By matching the IDs of the infected people’s cell phones to their identity, Antioquia seems to be doing just that.

“If I have a database with your name and address, and I also have this system, I can find, say, the identifiers that spend the night there. The search might show me other identifiers because you live with other people. But I only need to look at these identifiers’ movements to know who is each person: if one of them goes to school, it is a child; and if someone goes to your workplace, I can identify it as your own,” explains Andrés Velásquez, the main researcher of the report.

Morales, the pandemic manager in Antioquia, said in the press conference that “the tool does not tell us the name of the person, who they are, or if they are male or female. The only thing it tells us is their cell phone’s commercial identifier.”

But, as Karisma’s Andrés Velásquez says, identifying and tracking people is still possible. “A person who uses their cell phone a lot can be followed easily. If someone wants to know where a journalist, a lawyer, or a human rights defender are, it is just a matter of cross-checking their data.”

These concerns led Apple to announce that the next version of iOS, its mobile operating system, will force apps to request permission from users every time they want to access the device’s IDFA.

And a group of digital rights organizations managed to get Google fined for 50 million euros in France. In the court’s opinion, the constant monitoring enabled by these IDs goes against the users’ privacy rights.

Users can reset their advertising identifiers and prevent them from being sent targeted ads. However, it is not clear if this option stops the tracking altogether or only obfuscates the database so that the information collected in it cannot be associated with a single user.

The wrong tech

The WHO established several criteria for all applications and technological solutions that seek to contribute to curbing the virus: They must have limited time and scope, be tested and evaluated before being deployed, only collect data proportional to their objective, use the least amount of data possible, not be linked to any commercial operation, be voluntary, and be transparent and explained clearly to users.

Karisma says these technologies do not meet any of these parameters. “They are not voluntary, they were deployed without any prior test or evaluation, and the system and the decision-making that led to their deployment are not transparent. There is also no information about the algorithms used, nor about whether or not they were verified or validated by health authorities,” the report says.

Carolina Botero, executive director of Karisma, says that these solutions are symptomatic of the run-down approach with which Colombia has approached COVID technology. “In other countries, it takes months to launch technological solutions, as their implementation is publicly discussed. But in Colombia, there is a tendency to make hasty decisions without any transparency or public recourse, and with few control and monitoring options,” she says.

In the end, the problem is that Colombia risks not being able to take advantage of the potential that a technological solution can have to help not only to stop the virus but also to reopen the economy. Sending alarmist and imprecise warnings, the report says, “will cause many other people to ignore these messages later if, suddenly, Colombia manages to put together a well-planned and tested system.”